Life

What is Stockholm Syndrome?

Published

3 years agoon

Most people know the phrase Stockholm Syndrome from the numerous high-profile kidnapping and hostage cases – usually involving women – in which it has been cited.

The term is most associated with Patty Hearst, the Californian newspaper heiress who was kidnapped by revolutionary militants in 1974. She appeared to develop sympathy with her captors and joined them in a robbery. She was eventually caught and received a prison sentence.

But Hearst’s defence lawyer Bailey claimed that the 19-year-old had been brainwashed and was suffering from “Stockholm Syndrome” – a term that had been recently coined to explain the apparently irrational feelings of some captives for their captors.

More recently, the term was applied in media reports about the Natascha Kampusch case. Kampusch – kidnapped as a 10-year-old by Wolfgang Priklopil and held in a basement for eight years – was reported to have cried when she heard her captor had died and subsequently lit a candle for him as he lay in the mortuary.

While the term is widely known, the incident that led to its coinage remains relatively obscure.

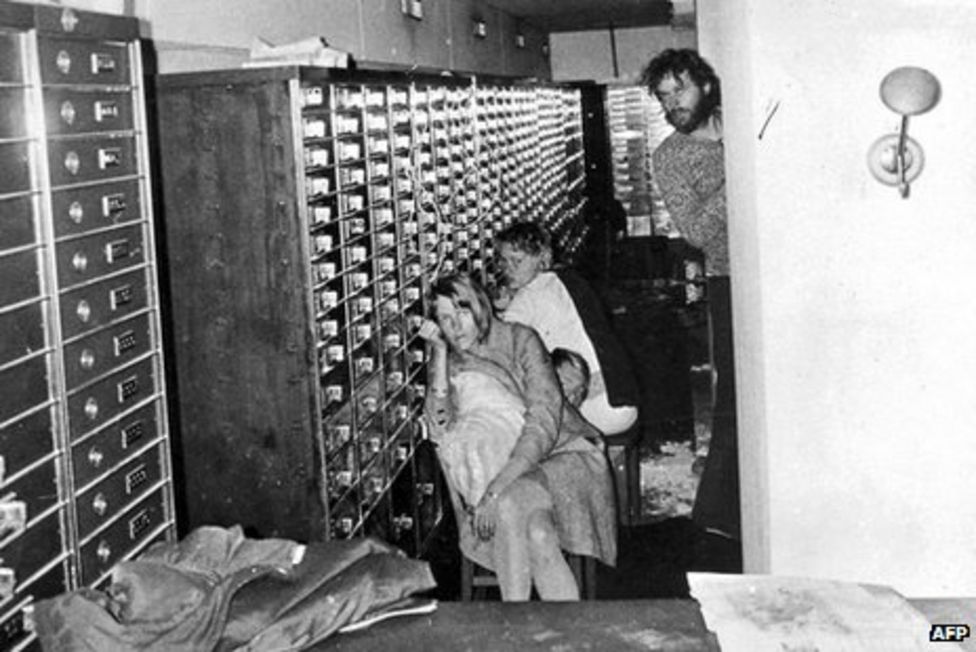

Outside Sweden, few know the names of bank workers Birgitta Lundblad, Elisabeth Oldgren, Kristin Ehnmark and Sven Safstrom.

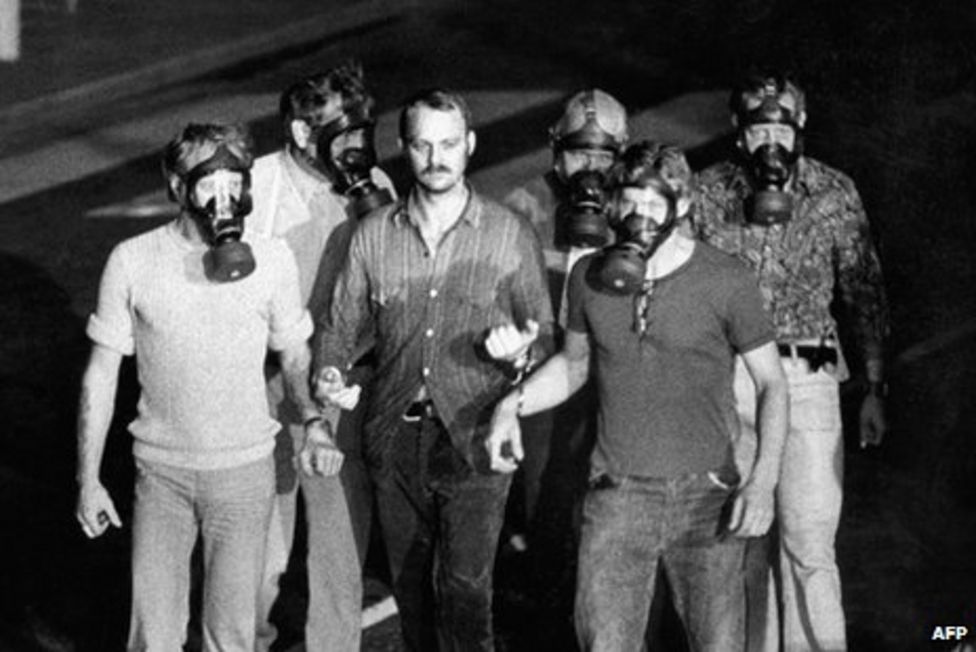

It was August 23, 1973, when the four were taken hostage in the Kreditbanken by 32-year-old career-criminal Jan-Erik Olsson – who was later joined at the bank by a former prison mate. Six days later when the stand-off ended, it became evident that the victims had formed some kind of positive relationship with their captors.

Stockholm Syndrome was born by way of explanation.

The phrase was reported to have been coined by criminologist and psychiatrist Nils Bejerot. Psychiatrist Dr Frank Ochberg was intrigued by the phenomenon and went on to define the syndrome for the FBI and Scotland Yard in the 1970s.

At the time, he was helping the US National Task Force on Terrorism and Disorder devise strategies for hostage situations.

His criteria included the following: “First people would experience something terrifying that just comes at them out of the blue. They are certain they are going to die.”

“Then they experience a type of infantilisation – where, like a child, they are unable to eat, speak or go to the toilet without permission.”

Small acts of kindness – such as being given food – prompts a “primitive gratitude for the gift of life,” he explains.

“The hostages experience a powerful, primitive positive feeling towards their captor. They are in denial that this is the person who put them in that situation. In their mind, they think this is the person who is going to let them live.”

But he says that cases of Stockholm Syndrome are rare.

So, what went on in the bank on Stockholm’s Norrmalmstorg square that enabled the captives to experience positive feelings towards their captors, despite fearing for their lives?

In a 2009 interview with Radio Sweden, Kristin Ehnmark explained: “It’s some kind of a context you get into when all your values, the morals you have change in some way.”

It was Ehnmark that, according to reports, built up the strongest relationship with Olsson. There were even erroneous reports afterwards that the pair had become engaged.

In one phone call from the bank’s vault to the country’s prime minister Olof Palme, Ehnmark begged to be allowed to leave the bank with the kidnappers. One of Olsson’s demands had been the delivery of a getaway car in which he planned to escape with the hostages. The authorities had refused.

Telling Palme that she was “very disappointed” with him, Ehnmark said: “I think you are sitting there playing chequers with our lives. I fully trust Clark and the robber. I am not desperate. They haven’t done a thing to us. On the contrary, they have been very nice. But you know, Olof, what I’m scared of is that the police will attack and cause us to die.”

American journalist Daniel Lang interviewed everyone involved in the drama a year later for the New Yorker. It paints the most extensive picture of how captors and captives interacted.

The hostages spoke of being well treated by Olsson, and at the time it appeared that they believed they owed their lives to the criminal pair, he wrote.

On one occasion a claustrophobic Elisabeth Oldgren was allowed to leave the vault that had become their prison but only with a rope fixed around her neck.

She said that at the time she thought it was “very kind” of Olsson to allow her to move around the floor of the bank.

Safstrom said he even felt gratitude when Olsson told him he was planning to shoot him – to show the police understood he meant business – but added he would make sure he didn’t kill him and would let him get drunk first.

“When he treated us well, we could think of him as an emergency God,” he went on to say.

Stockholm Syndrome is typically applied to explain the ambivalent feelings of the captives, but the feelings of the captors change too.

Olsson remarked at the beginning of the siege he could have “easily” killed the hostages but that had changed over the days.

“I learned that the psychiatrists I interviewed had left out something: victims might identify with aggressors as the doctors claimed, but things weren’t all one way,” wrote Lang.

“Olsson spoke harshly. ‘It was the hostages’ fault,’ he said. ‘They did everything I told them to do. If they hadn’t, I might not be here now. Why didn’t any of them attack me? They made it hard to kill. They made us go on living together day after day, like goats, in that filth. There was nothing to do but get to know each other.'”

The notion that perpetrators can display positive feelings toward captives is a key element of Stockholm Syndrome that crisis negotiators are encouraged to develop, according to an article in the 2007 FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin. It can improve the chances of hostage survival, it explained.

But while Stockholm syndrome has long been featured on police hostage negotiating courses, it is rarely encountered, says Hugh McGowan, who spent 35 years with the New York Police Department.

McGowan was the commanding officer and chief negotiator of the Hostage Negotiation Team, which was set up in April 1973 in the wake of a number of hostage incidents that took place in 1972 – the bank heist that inspired the film Dog Day Afternoon, an uprising that came to a violent end at Attica prison in New York and the massacre at the Munich Olympics.

“I would be hard pressed to say that it exists,” he says. “Sometimes in the field of psychology people are looking for cause and effect when it isn’t there.

“Stockholm was a unique situation. It occurred at around the time when we were starting to see more hostage situations and maybe people didn’t want to take away something that we might see again.”

He acknowledges that the term gained currency partly because of the bringing together of the fields of psychology and policing in the field of hostage negotiating.

There are no widely accepted diagnostic criteria to identify the syndrome, which is also known as terror-bonding or trauma bonding and it is not in either of the two main psychiatric manuals, The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders and the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD).

But the underlying principles of how it works can be related to different situations, say some psychologists.

“A classic example is domestic violence, when someone – typically a woman – has a sense of dependency on her partner and stays with him,” says psychologist Jennifer Wild, a consultant clinical psychologist at the University of Oxford.

“She might feel empathy rather than anger. Child abuse is another one – when parents emotionally or physically abuse their children, but the child is protective towards them and either doesn’t speak about it or lies about it.”

Forty years on and the term is evoked nearly every time an abductee is found after many years out of public sight. Some argue that its very nature implies a criticism of the survivor – a weakness perhaps.

In a 2010 interview with the Guardian, Kampusch rejected the label of Stockholm Syndrome, explaining that it doesn’t take into account the rational choices people make in particular situations.

“I find it very natural that you would adapt yourself to identify with your kidnapper,” she says. “Especially if you spend a great deal of time with that person. It’s about empathy, and communication. Looking for normality within the framework of a crime is not a syndrome. It is a survival strategy.”

Source: BBC

You may like

Life

Start Your Day Right: The Benefits of a Clutter-Free Desk

Published

1 year agoon

August 18, 2024By

Samy Deyyab

In today’s fast-paced world, it’s easy for our workspaces to become cluttered with papers, gadgets, and miscellaneous items. While this might seem harmless, a disorganized desk can negatively impact your focus, productivity, and even emotional well-being. Fortunately, the solution is simple: start your day by cleaning your desk.

The Science Behind a Clean Desk

Why does tidying up make such a difference? A key reason lies in how our brains process visual information. Studies like those conducted at Princeton University have demonstrated that cluttered environments overwhelm the brain’s visual cortex, making it harder to concentrate and process information. This clutter-induced distraction leads to irritability, stress, and reduced productivity.

Moreover, a study by DePaul University revealed that clutter is a significant predictor of procrastination. When our environment is chaotic, we tend to put off tasks, leading to a cycle of stress and decreased quality of life. Another study from UCLA found that people who perceive their homes as cluttered experience higher levels of cortisol, the stress hormone, which is linked to negative health outcomes like depression and anxiety.

By taking a few minutes each day to organize your workspace, you can significantly improve your mental clarity, emotional stability, and decision-making abilities.

Practical Steps to Declutter

1. Start small:

Begin with the most frequently used areas, such as your desk or computer desktop. This approach makes the task manageable and prevents you from feeling overwhelmed. Use the five-minute rule: dedicate just five minutes to tidying up. Often, this small commitment leads to much more progress than anticipated.

2. Embrace digital tools:

Technology can be a great ally in staying organized. Utilize digital task management apps like Todoist or Trello to keep track of your to-do lists and deadlines. Cloud storage solutions like Google Drive or Dropbox can help you declutter your physical space by digitizing important documents. By leveraging these tools, you can physically and digitally maintain a clean and organized workspace.

3. Schedule regular maintenance:

Staying organized is an ongoing process. Set aside 10-15 minutes each day for “maintenance” time. This could be as simple as filing away papers, deleting unnecessary files from your computer, or tidying up your workspace. Consistency is key, and this small daily habit can prevent clutter from accumulating.

4. Automate Routine Tasks:

Automation can also help keep your workspace organized. Use tools like Zapier to automate repetitive tasks, such as sorting emails or backing up files. By reducing the manual work involved in maintaining your digital space, you free up mental bandwidth for more important tasks.

5. Make It Fun:

For those who find cleaning a chore, turn it into a social activity. At work, consider organizing team-wide “spring cleaning” days where everyone tidies up their workspace together, perhaps with music or snacks. For your workspace, set a timer and challenge yourself to see how much you can accomplish in that time. Making the process enjoyable can increase your motivation to keep your space tidy.

The Broader Impact of Decluttering

A clean workspace does more than just make you feel better in the moment—it sets the stage for long-term success. By removing physical obstacles, you also clear mental obstacles, leading to improved focus, better decision-making, and a greater sense of control over your environment. This psychological boost can extend to other areas of your life, helping you tackle challenges with greater confidence and clarity.

Incorporating technology into your decluttering efforts not only streamlines the process but also helps you stay organized in the long run. Whether it’s through digital task management, automation, or regular maintenance, these tools can play a crucial role in maintaining a clear, focused, and productive work environment.

In a world filled with distractions, maintaining a clean and organized workspace is more important than ever. By starting your day with a simple act of decluttering, you can harness the power of emotional intelligence to improve your focus, reduce stress, and enhance your overall productivity. So the next time you’re feeling overwhelmed, take a few minutes to tidy up your desk. Your mind—and your work—will thank you.

Life

Mind Games in Marketing: How Companies Influence Our Choices

Published

2 years agoon

December 17, 2023By

Jimmy Walter

In the ever-changing world of marketing and design, brands have developed sophisticated strategies to influence consumer behavior and perceptions. From the medicine we take to the cars we drive, the power of branding shapes every aspect of consumer choice.

The Psychological Influence of Branding

Branding is more than just a marketing tool; it’s a psychological phenomenon that can significantly shape our actions and physiological responses. A striking example is the effectiveness of medicines based on their branding.

Identical ingredients in a branded medicine like Tylenol and its generic counterpart can yield different perceptions of effectiveness due to the price or packaging color. Similarly, the mere presence of a familiar logo, such as MasterCard, can trigger customers to spend up to 30% more. These examples underscore how branding taps into our subconscious, influencing our decisions and experiences without explicit awareness.

Branding is a psychological phenomenon, subtly shaping our choices and experiences.

Beyond its psychological effects, branding has evolved into a placebo, offering more than a product. Companies now sell a sense of belonging and identity. This phenomenon is not new; it traces back to ancient times when craftsmen would imprint symbols on their goods as a mark of authenticity and origin.

However, modern branding has taken this concept to new heights. By crafting a unique brand image and narrative, companies reel in consumers, offering them a sense of inclusion in a particular ‘tribal’ group. This powerful tool leverages our innate desire for social belonging and identity, driving our purchasing decisions.

The Role of Visual Signaling

A critical aspect of branding is its reliance on visual elements to convey a product’s quality and benefits. From the stripes on toothpaste tubes to the design of food packaging, visual signals play a pivotal role in shaping consumer perceptions and trust.

However, this visual shorthand can sometimes cross ethical boundaries, leading to deceptive practices. For example, car companies may add fake vents to their designs, creating an illusion of enhanced performance. This manipulation highlights brands’ fine line between honest representation and misleading consumers for increased sales.

Visual elements in branding are pivotal in forging consumer trust and perception.

One of the more cunning tactics in the branding playbook is the creation of artificial scarcity. Brands like Apple or certain fashion labels release limited quantities of new products, generating a fear of missing out and driving up demand.

This strategy capitalizes on human psychology, where we desire what we perceive as scarce or exclusive. However, this often leads to ethical dilemmas, as companies intentionally limit supply not due to production constraints but as a marketing ploy.

The Ethics of Branding

The ethics of branding are a complex and nuanced topic. While branding can foster a sense of community and enhance the consumer experience, it often prioritizes company profits over truthful representation.

Consumers should be aware of these tactics, recognizing that brands are ultimately tools for increasing sales, not benevolent entities safeguarding values or social causes. For instance, when a brand aligns with political or social issues, it is often a calculated move to tap into consumer sentiments and loyalty rather than a genuine commitment to the cause.

Ethically navigating branding’s power demands informed consumer awareness and discernment.

In conclusion, the influence of branding on our daily lives is profound and multifaceted. From shaping our perceptions of product effectiveness to fostering a sense of identity and belonging, branding has become an integral part of the consumer experience.

However, it’s crucial for consumers to remain aware of companies’ tactics and understand the line between clever marketing and manipulative practices. By doing so, we can make more informed choices, recognizing the power of branding while remaining cognizant of its potential to mislead and manipulate.

As we navigate this complex landscape, it’s essential to remember that while branding can create meaningful experiences, it should never compromise our ability to discern reality from marketing fiction.

Life

2023: A Year of Dire Warnings and Glimmering Hope

Published

2 years agoon

December 16, 2023By

Amanda Brown

As 2023 came to a close, it left behind a complex environmental legacy that was both marked by extreme weather events and innovative breakthroughs. On the one hand, the world witnessed the devastating consequences of climate change, with scorching heat waves, devastating wildfires, and rising sea levels disrupting human life and ecosystems.

On the other hand, there were also signs of hope as nations stepped up their efforts to combat climate change and protect biodiversity, and innovative technologies emerged to address environmental challenges.

Climate Crisis

2023 was one of the hottest years ever recorded, with temperatures edging closer to the 1.5°C threshold set by the Paris Climate Agreement. Heatwaves ravaged Europe, North America, and Asia, pushing temperatures above 40°C in cities like London and Paris. Forest fires burned across continents, turning vast swathes of land into infernos.

The melting of polar and mountain glaciers accelerated, with the extent of Arctic sea ice reaching a record low in September and the Greenland ice sheet losing a staggering 26 billion tons of ice in a single day.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) issued a stark warning this year, stating that human activity is fundamentally altering the climate system in unprecedented and often irreversible ways.

Carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere reached 419 parts per million in 2023, surpassing the previous year’s record and cementing the reality of a warming planet.

Conflicts and Challenges

Economists have called for policies that incentivize a shift towards low-emission energy sources, such as carbon taxes, to address the market failures contributing to the climate crisis.

The ongoing war in Ukraine has raised concerns about the impact of conflicts on the global transition to clean energy. Will the conflict lead to increased investment in fossil fuels, hindering progress towards cleaner energy sources? Or will it catalyze the acceleration of the adoption of renewable energy, demonstrating its resilience and potential?

Despite these challenges, the world will witness a noticeable increase in the use of renewable energy sources in 2023. Countries like Germany and Denmark achieved record shares of clean energy in their electricity grids, highlighting the viability and potential of solar and wind power. Investment in solar energy surged, with installations reaching new heights around the globe.

A Glimmer of Hope

Amidst the dire warnings and extreme weather events, there were signs of hope and resilience. Global efforts to combat climate change continued to gain momentum in 2023, with the focus shifting towards implementing radical emission reductions to keep global warming within 1.5°C. Interest in developing carbon capture and storage technologies also intensified, demonstrating the commitment to addressing the root cause of the climate crisis.

The World Climate Summit (COP28) in Dubai provided a platform for nations to unite in their efforts to address climate change and protect biodiversity. The summit highlighted the need for a fair and equitable approach to addressing the climate crisis, ensuring that developing nations have access to the necessary resources to adapt to and mitigate the effects of climate change.

A Sustainable Future

The year 2023 saw the development of innovative technologies and solutions to address environmental challenges. Pioneering projects like harvesting solar energy using water canals in India and growing “alternative meat” in Singapore laboratories demonstrated the potential for transformative innovation in the realm of sustainability.

Electric vehicles gained broader adoption in 2023, as major automakers announced ambitious plans to phase out conventional motor vehicles. While carbon capture and storage technologies are still in their early stages, they promise to mitigate the effects of greenhouse gas emissions and contribute to achieving global net-zero emissions by 2050.

On a societal level, 2023 witnessed a surge in popular movements and youth initiatives demanding action on environmental issues. From climate strikes calling for serious action from world leaders to local groups organizing cleanups and tree plantings, individuals worldwide came together to create positive change.

As we bid farewell to 2023, we are left with a complex environmental legacy. While the challenges remain daunting, the year also witnessed inspiring innovations and a growing commitment to addressing the climate crisis and protecting biodiversity.

The path forward is uncertain, but the glimmer of hope offers a roadmap towards a sustainable future.

In the modern work environment, many of us find ourselves tethered to our desks, immersed in the digital world for the better part of our day. This sedentary lifestyle can lead to a host of health issues, from obesity to heart disease.

However, staying fit while working a desk job isn’t just a possibility; it’s necessary to maintain overall health and well-being.

Here’s a comprehensive guide to staying active and healthy, even in front of a computer.

Workplace Wellness

First and foremost, setting up an ergonomic workspace is crucial. Ergonomics, the science of designing the workplace to fit the user’s needs, aims to improve efficiency and reduce discomfort. Ensure that your chair supports your lower back, your feet are flat on the ground, and your computer screen is at eye level to avoid strain.

An ergonomic keyboard and mouse can also prevent repetitive strain injuries. Investing in a standing desk or an under-desk elliptical can be beneficial, too.

Mini Workouts

Integrating mini-workouts into your daily routine can be remarkably effective. Take a five-minute break every hour to stretch or do a quick set of exercises.

Desk-based stretches, chair squats, leg lifts, or even simple neck and shoulder stretches can keep your muscles active.

These short bursts of activity improve physical health and boost mental alertness and productivity.

Walk and Talk

Incorporate movement into your communication. Opt for walking meetings instead of sitting in a conference room.

If you’re on a call, walk around your office or outside if possible. This not only breaks the monotony of sitting but also invigorates your mind.

Healthy Eating at Work

Diet plays a significant role in staying fit. Avoid the temptation of snacking on junk food. Opt for healthier options like fruits, nuts, or yogurt.

Keep a water bottle at your desk to stay hydrated. If you’re prone to forgetting, set reminders to drink water throughout the day.

Stress Management

Prolonged computer work can be mentally taxing. Practice mindfulness and stress management techniques like deep breathing or meditation during breaks. Apps that guide you through short meditation sessions can be easily incorporated into your workday.

Incorporating these practices into your daily work routine can significantly improve your fitness and overall health. Remember, it’s the small changes that make a big difference over time.

With a combination of ergonomic awareness, mini workouts, movement-integrated communication, healthy eating, and mindfulness, you can maintain a high level of fitness, even while working a desk job.

Stay active, eat well, and engage your mind for a healthier work life.

Life

How to Kickstart Your Motivation and Thrive

Published

2 years agoon

December 11, 2023By

Mona Rossy

As we navigate the prolonged waves of the pandemic, a common narrative has emerged among individuals from all walks of life. Many are finding themselves trapped in a state of stagnation and emptiness, a phenomenon that has become all too familiar in our current global situation.

This feeling, often termed ‘languishing,’ has become a shared experience, resonating deeply with people worldwide.

The Double-Edged Sword of Rest

The feeling of stagnation or immobility, frequently accompanied by a sense of emptiness, is what languishing encapsulates. It’s as if life is being viewed through a foggy lens, where days blend into one another without a sense of progress or fulfillment.

This feeling gained widespread recognition during the pandemic, offering individuals a label for their experiences and a sense of solidarity with others in the same boat.

The initial prescription was rest in response to this widespread sense of burnout and emotional fatigue. Physical, emotional, social, and spiritual rest were all emphasized as crucial for recovery.

However, an extended period of rest has its pitfalls. It can lead to a state of inertia where, despite feeling physically recovered, a psychological sense of disconnection and listlessness persists.

Enter the concept of behavioral activation, a strategy developed in the 1970s. This approach challenges the notion that motivation precedes action. Instead, it posits that taking action, even in small ways, can catalyze motivation. This idea is particularly potent when feeling stuck, as it encourages movement and progress, however incremental.

Moving Beyond Forced Positivity

Behavioral activation contrasts the now-debunked concept of forced positivity – the idea that simply thinking positive thoughts can lead to happiness and success. Current understanding suggests that controlling thoughts and feelings often has the opposite effect. Instead, behavioral activation focuses on engaging in meaningful activities and aligning actions with values and interests, regardless of the prevailing mood or emotional state.

A key aspect of moving beyond languishing involves a shift in mindset. It’s about recognizing and accepting negative emotions without allowing them to dictate one’s actions. This means giving oneself permission to feel low or unmotivated but not seeing these feelings as permanent or insurmountable.

Activation Energy: The Initial Push

The concept of ‘activation energy’ is crucial in this context. It refers to the effort required to initiate a task or activity. During times of stress or emotional fatigue, like in the current pandemic, this activation energy might be higher. Recognizing and accepting this can be the first step in overcoming inertia.

Once the initial resistance is overcome, momentum can start to build. Engaging in minor activities can create a positive feedback loop where action begets more action. This process can gradually lead to an improvement in mood and a sense of accomplishment.

The Role of Small Steps

When dealing with the overwhelming feeling of languishing, small steps matter. It’s about setting manageable goals and celebrating minor victories. Whether making a phone call, organizing a walk with a friend, or dedicating time to a hobby, each small action is a step away from stagnation.

It’s essential to remember that the state of languishing is not permanent. As daunting as it may seem to initiate change while feeling stuck, the effort is worthwhile. The more we engage in actions aligned with our interests and values, the easier it becomes to break free from the rut.

As we continue to face the challenges brought on by the pandemic, it’s crucial to recognize the impact of languishing on our mental health. We can find a way out of the fog by embracing behavioral activation and acknowledging our emotions without letting them control us. It’s about taking that first step, however small, and building momentum from there. In doing so, we can rediscover our motivation and sense of purpose, moving towards a brighter, more fulfilling future.

Life

Echoes of the Mind: The Power of Inner Dialogue

Published

2 years agoon

September 15, 2023By

Mona Rossy

Have you ever caught yourself mumbling under your breath about an annoying task or silently cheering yourself on before a big presentation? Congratulations, you’re part of the majority!

The world of self-talk, that little voice inside us, holds more power and potential than most realize. Dive in to unravel the mysteries of this everyday phenomenon.

The Ubiquity of Inner Conversations

It’s a bright morning, and as you scramble to silence the blaring alarm, a soft mutter escapes, “Why on earth did I set it so early?” Moments later, while brushing your teeth, the mirror reflects a contemplative face: “Maybe it’s time for a haircut. Or perhaps not?”

Welcome to the realm of self-talk, an experience almost all of us can relate to. This narration within our heads is as much a part of us as our heartbeat.

The Evolution of Self-Talk

Children, especially those at play, often verbalize their thoughts, openly engaging with imaginary friends or narrating their adventures. This isn’t merely child’s play, though.

Renowned Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky pinpointed this kind of vocal self-talk as a cornerstone of children’s emotional and behavioral development. By replaying adult-like conversations, children learn to manage their behaviors and emotions.

As adulthood transitions, this external chatter turns inward, evolving into an intimate inner dialogue. Yet, its function remains pivotal.

It aids us in planning and decision-making and even offers that little push of motivation we so often need.

What We Tell Ourselves

Engaging in self-talk isn’t just a pastime; it genuinely affects our psyche. Let’s split this into two – the boon and the bane.

The Boon: Imagine gearing up for a tennis match. A gentle whisper of “I’ve got this, focus on the serve” can amp up concentration levels, translating into a stellar performance. Similarly, addressing oneself by name, a technique known as distanced self-talk can work wonders.

Picture yourself preparing for a nerve-wracking public speech. A motivating “Alex, you’ve got this!” can instantly dial down the anxiety, making the task seem less daunting.

The Bane: Like a coin, self-talk has another side. Negative chatter, “Why am I always messing up?”, can be slippery.

Too much of this, and we risk plunging into the depths of anxiety and depression. It’s akin to having a constant critic inside your head, scrutinizing every move.

Navigating the World of Self-Talk with CBT

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, or CBT for short, shines a beacon of hope for those entangled in the web of negative self-talk.

This therapeutic approach focuses on recognizing, challenging, and then reshaping these negative narratives into neutral or positive reflections. Armed with these tools, one can cultivate a healthier, more compassionate relationship with that ever-present inner voice.

Embrace Your Inner Voice

There’s a saying, “Be careful how you speak to yourself because you are listening.” Embracing and fine-tuning our self-talk is more than just self-awareness; it’s an act of self-love. The next time you catch yourself in a silent conversation, remember its power.

Use it as a tool for growth, motivation, and emotional well-being. After all, that inner voice isn’t going anywhere. Why not make it a friend?

Fenikss Casino: Kā Veikt Reģistrāciju un Pirmo Iemaksu

Slottyway PL Nowoczesne kasyno online dla polskich graczy

Unlocking the Power of Smart Devices: What You Need to Know

Is a New Era of United States-China Space Collaboration Possible?

Can smart technology unlock a sustainable future?

Start Your Day Right: The Benefits of a Clutter-Free Desk

Emerging Titan: India’s Strategic Move on The Global Chessboard

Use these services to get free cloud space

From Unity to Split: Is This Libya’s New Chapter?

New Revolution in MENA Region: FAST and Ad-Supported

Navigating The New Silk Road: A Ten-Year Retrospective

How Technology is Reshaping Modern Warfare

Trending

-

Poltics2 years ago

Poltics2 years agoEmerging Titan: India’s Strategic Move on The Global Chessboard

-

Technology3 years ago

Technology3 years agoUse these services to get free cloud space

-

Poltics2 years ago

Poltics2 years agoFrom Unity to Split: Is This Libya’s New Chapter?

-

Technology2 years ago

Technology2 years agoNew Revolution in MENA Region: FAST and Ad-Supported

-

Poltics2 years ago

Poltics2 years agoNavigating The New Silk Road: A Ten-Year Retrospective

-

Technology2 years ago

Technology2 years agoHow Technology is Reshaping Modern Warfare