Poltics

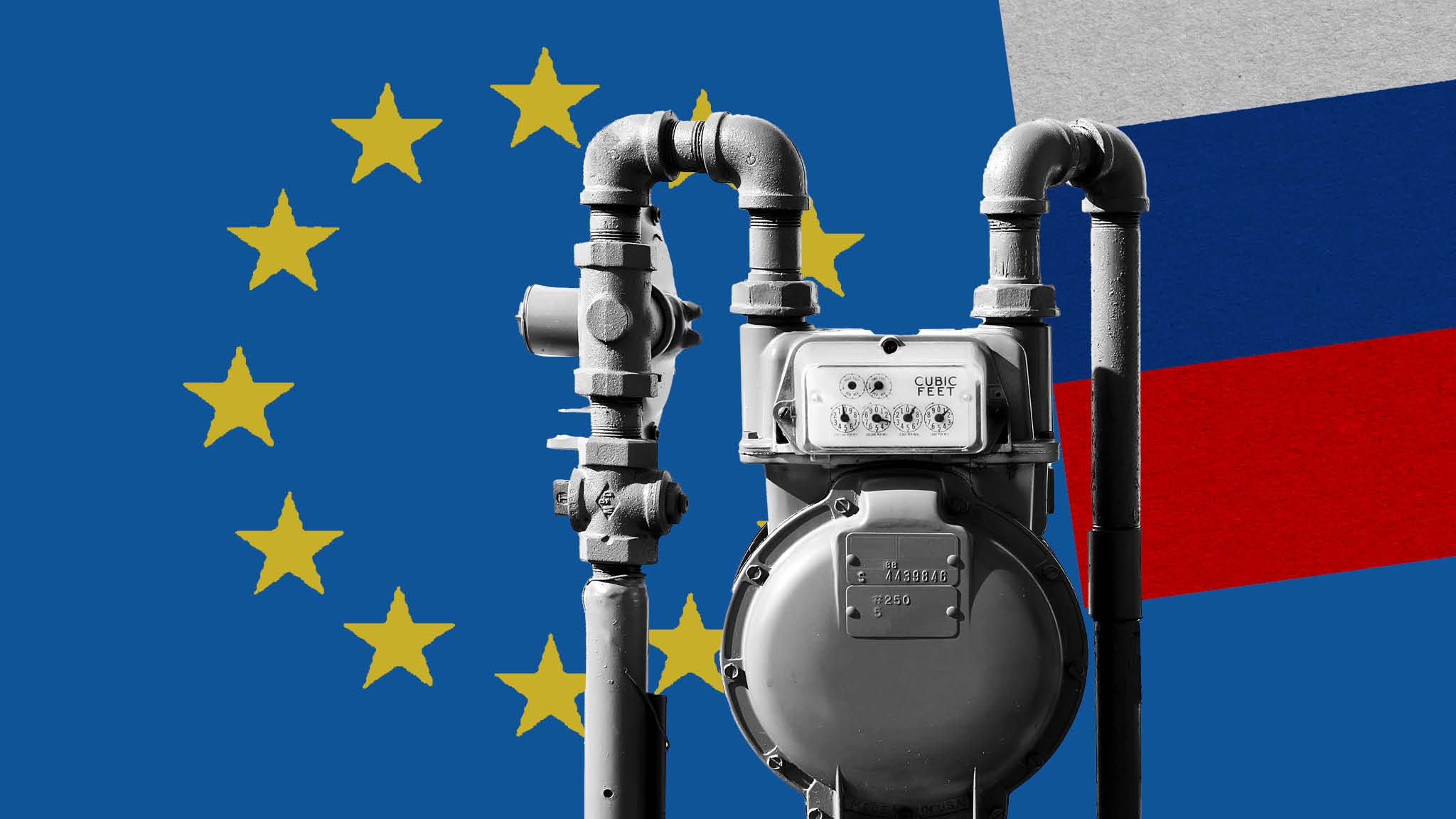

Europe is still dependent on Russian nuclear energy

Published

3 years agoon

Russia’s nuclear fuel industry remains conspicuously untouched by European sanctions more than seven months into the Kremlin’s war in Ukraine — much to the dismay of Kyiv officials and environmental campaigners.

Despite eight rounds of sanctions, targeted measures against energy exports and calls from Ukraine to impose a full embargo on nuclear trade, shipments of nuclear fuel to EU member states continue to make their way from Russia.

Ariadna Rodrigo, EU sustainable finance manager at environmental group Greenpeace, told CNBC via telephone that it is “absolute madness” for the bloc to continue bankrolling the Kremlin by ignoring Russia’s nuclear fuel trade.

“If EU governments are serious about stopping war, they need to cut the European nuclear industry’s umbilical cord to the Kremlin and focus instead on accelerating energy savings and renewables,” Rodrigo said.

On presenting its latest sanctions package, the European Commission did not propose targeting the trade of Russian nuclear fuel. The EU’s executive arm has previously targeted Russian oil, gas and coal as part of a broader strategy to ratchet up the economic pressure on the Kremlin.

Hungary and Bulgaria were the most vocal in opposing sanctions on Russian uranium and another nuclear tech last week, according to Rodrigo.

More than seven months into the Kremlin’s war in Ukraine, Russia’s nuclear fuel industry remains conspicuously untouched by European sanctions.

The commission has repeatedly condemned Russia’s war in Ukraine, accusing President Vladimir Putin of using energy as a weapon to drive up commodity prices and sow uncertainty across the 27-nation bloc. Moscow denies weaponizing energy supplies.

The few EU prohibitions on Russia’s nuclear energy sector that are in place, such as a port access ban on Russian-flagged vessels for the transport of nuclear fuel, contain numerous loopholes and campaigners argue much tougher measures are needed to reduce the bloc’s dependency on Russian nuclear services.

That sentiment is echoed by Kyiv.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy said in early August that he had spoken with European Council President Charles Michel about the need for the EU to impose sanctions on the Russian nuclear industry.

“Russian nuclear terror requires a stronger response from the international community – sanctions on the Russian nuclear industry and nuclear fuel,” Zelenskyy said via Twitter at the time.

More recently, a top economic advisor to Zelenskky doubled down on this message, saying it was “extremely important to impose sanctions, not only on Russian oil.”

“Oil, gas, uranium and coal, all this should be banned. Because they are using this money in order to finance this war,” Oleg Ustenko said in late September, according to The Associated Press.

Russia’s energy influence goes beyond oil and gas

In April, a European Parliament resolution called for an “immediate” embargo on Russian imports of nuclear fuel and urged member states to stop working with Russia’s state-run nuclear giant Rosatom on existing and new projects.

But Russia is a dominant player in the global nuclear fuel market and any move to break the EU’s reliance on its services would likely be far from pain-free, particularly with Rosatom at the heart of Europe’s dependency.

Backed by Putin, Rosatom not only dominates the civilian industry but is also in charge of Russia’s nuclear weapons arsenal and is currently overseeing the occupied Zaporizhzhia nuclear power station in Ukraine.

Despite eight rounds of sanctions, shipments of nuclear fuel to EU member states continue to make their way from Russia.

There are 18 Russian nuclear reactors in Europe, in countries including Finland, Slovakia, Hungary, Bulgaria and the Czech Republic. All of these reactors rely on Rosatom for the supply of nuclear fuel and other services.

Underlining the scale of Russia’s nuclear energy influence in some member states, even as the Kremlin’s onslaught in Ukraine continues, Hungary in late August announced the construction of two new nuclear reactors by Rosatom.

Moscow accounted for almost one-fifth (19.7%) of the EU’s uranium imports last year, according to the latest available data from the Euratom Supply Agency. Only Niger (24.3%) and former Soviet republic Kazakhstan (23%) were bigger suppliers of uranium to the bloc.

The EU paid around 210 million euros ($203.7 million) to import raw uranium from Russia last year, according to estimates reported by Investigate Europe, and another 245 million euros was paid to import uranium from Kazakhstan, where mining of the nuclear fuel is controlled by Rosatom.

“We are talking about a serious amount of money here,” Greenpeace’s Rodrigo told CNBC, noting that these estimates only accounted for uranium imports and the EU’s dependency covers services across the supply chain.

Asked to what extent Europe’s uranium imports from Russia undermines its efforts to encourage others to stop importing Russian energy, Rodrigo replied: “The fact that we are not discussing this properly just shows the double standards of the EU.”

How ‘green’ is nuclear energy?

Advocates of nuclear power argue it has the potential to play a major role in helping countries generate electricity while slashing carbon emissions and reducing their reliance on fossil fuels.

However, critics argue that nuclear power is an expensive and harmful distraction to faster, cheaper and cleaner alternatives. Instead, environmental campaign groups argue technologies such as wind and solar should be prioritized in the planned shift to renewable energy sources.

As part of the EU’s taxonomy — a mechanism that defines which investment options can be considered “green” — the bloc controversially recognized nuclear power and gas, a fossil fuel, as sustainable under some circumstances.

Austria on Monday launched a lawsuit against the EU and is seeking help from allies over the bloc’s labelling of nuclear power and gas as sustainable investment options, calling it “irresponsible and unreasonable.”

The EU has acknowledged the legal action but said it would not comment on the substance of the case.

Source: CNBC

You may like

-

From Geopolitical Challenges to Opportunities: EU’s Tech Game Plan

-

Rethinking Africa’s Destiny: Geopolitics and the Coup Phenomenon

-

Challenges and Opportunities: Turkey’s Election and The Future of EU-Turkey Relations

-

A strong step towards climate action in Europe

-

Is the end of Dollar dominance globally near?

-

European Parliament passes groundbreaking Crypto Regulations

Poltics

Is a New Era of United States-China Space Collaboration Possible?

Published

1 year agoon

August 20, 2024By

Amanda Brown

In the fall of 1958, President Dwight D. Eisenhower took a visionary step by proposing to the United Nations that outer space should be explored for peaceful purposes, with international cooperation at its core.

Senator Lyndon B. Johnson, who was in office then, continued this idea by envisioning space as a place where nations could put aside their differences and cooperate for the benefit of all. Johnson, who later became President, reiterated this vision in a 1967 letter to the Senate, emphasizing that space cooperation could help avoid conflicts and foster peace on Earth.

The historic Apollo-Soyuz docking in July 1975 became a symbol of this ideal. American astronauts and Soviet cosmonauts came together from two opposing superpowers in a moment of unity that captivated the world. NASA astronaut Tom Stafford, who participated in the mission, remarked that opening the hatch between the two spacecraft was like opening a “new era” back on Earth.

The Present State of Space Diplomacy

Fast forward to today, and the International Space Station (ISS) is a testament to multinational collaboration in space. Despite geopolitical tensions, the partnership among the United States, Europe, Canada, Japan, and Russia has endured, requiring joint engineering efforts and mutual reliance. The ISS is a shining example of what can be achieved when nations work together in space diplomacy.

However, the cooperative spirit that once drove space exploration is now facing significant challenges. Rising tensions between the United States, Russia, and China have overshadowed the original ideals of space collaboration. Space is no longer seen solely as a domain for scientific exploration but as a potential battlefield for military conflict. Although the United States and 42 other nations have signed the Artemis Accords, a set of principles for peaceful space exploration, key spacefaring nations like China and Russia have not joined these accords, highlighting the growing divide.

A Disappointing Setback

Both the United States and China have ambitious plans for lunar exploration, aiming to establish permanent bases on the moon. The United States, alongside its allies, is developing a lunar base and an orbiting lunar space station. Meanwhile, China, in collaboration with Russia and other nations, is pursuing a similar project called the International Lunar Research Station.

These parallel efforts, with little to no cooperation between the two groups, mark a significant departure from the collaborative spirit of the past. The Apollo-Soyuz handshake, once a symbol of unity, now seems like a distant memory. The question arises: What happened to the spirit of cooperation that once united even the most adversarial nations?

The Need for a New Beginning in US-China Space Cooperation

Despite the growing tensions and challenges, it is crucial to remember that similar dynamics existed in the past, yet leaders still chose to work together for the greater good. The United States and China must find a way to rekindle that spirit of cooperation, starting with small, achievable goals.

One potential starting point is the UN Rescue and Return of Astronauts Agreement, established in 1968. This agreement commits nations to assist astronauts in distress, regardless of their origin. While this principle is noble, it lacks practical implementation. For instance, without standardized equipment and procedures, it is unlikely that astronauts from different nations could effectively assist each other in an emergency.

To address this, a bilateral working group between NASA and China’s National Space Administration (CNSA) should be established to prepare for joint rescue operations. This initiative would not only improve communication between the two space communities but also ensure readiness for potential rescue missions, which could have profound benefits in times of need.

Building on Small Successes

Once this initial collaboration is established, further bilateral agreements should be pursued. These could include mutual use of lunar communication and navigation services, as well as agreements on providing essential resources like power, habitats, and transportation.

For the United States, a critical step toward fostering cooperation would be the repeal of the Wolf Amendment, which was enacted in 2011 to prevent the transfer of space technology to China. This amendment has not slowed China’s space advancements but has hindered potential collaboration. Removing this barrier could open the door to more meaningful exchanges between NASA and CNSA.

On the other hand, China should commit to greater transparency and communication regarding its space activities. Taking a leading role in space sustainability and joining global efforts to prevent destructive space activities would build trust and pave the way for future cooperation.

A Call for Renewed Cooperation

Eisenhower and Johnson understood the importance of space cooperation in preventing conflict and fostering peace. Their vision is more relevant than ever as the world faces new challenges in space exploration. The United States and China must take swift action to initiate cooperation in space, setting the stage for a more unified and peaceful future in the final frontier.

In the dynamic realm of politics, where change is the only constant, a new force is quietly reshaping the landscape: artificial intelligence (AI). Forget charismatic leaders or groundbreaking policies; the driving force of the impending revolution is a technology that was once confined to science fiction.

As AI seamlessly integrates into our daily lives, politics stands on the brink of transformation. Let’s delve into how AI is poised to redefine how we elect leaders, shape societies, and navigate the intricate tapestry of modern politics.

The Dawn of a New Era

As the digital dawn breaks, the traditional paradigms of politics are being challenged, and AI emerges as the beacon of change. Imagine a political arena where campaigns are meticulously crafted for individual voters, ushering in an era of hyper-personalization.

In this world, AI analyzes abundant data on demographics, interests, and voting history to generate messages that resonate uniquely with each voter. Blanket advertising is replaced with precisely targeted content on social media, emails, and streaming services, transforming the voter-candidate relationship.

This promises a more engaged electorate and sparks a paradigm shift in election outcomes as voters find resonance in messages tailored precisely to their concerns.

In the heartbeat of any political campaign lies fundraising, and AI is set to revolutionize this financial dance. By delving into donor data, AI predicts potential supporters and suggests the most effective fundraising strategies.

The implications are profound: candidates armed with sophisticated AI tools could gain a significant financial advantage. Yet lurking in the shadows are concerns about the potential influence of wealth and special interest groups wielding AI to sway the electoral scales.

AI’s Role in Political Evolution

Beyond individual campaigns, AI has the power to reshape the political party landscape. Through analyzing public opinion data and identifying emerging trends, AI could give birth to new political entities tailored to specific demographics or issues.

While this promises a more diverse political tapestry, it simultaneously raises questions about the stability of coalitions and the effectiveness of governance in this brave new world.

AI emerges as the ultimate political educator in an age where information floods our senses. AI offers personalized news feeds and summaries of complex issues to address the challenge of information overload.

AI curates content aligned with each voter’s interests and political leanings by scrutinizing news articles, social media posts, and various information sources. The result? A more informed electorate and citizenry are actively engaged in the political process.

AI’s Potential for Manipulation

While the promises of AI in politics are vast, so are the risks. A significant concern is AI’s potential to manipulate voters. Micro-targeting individuals with misleading or inflammatory content could tilt public opinion and compromise the integrity of democratic processes.

Additionally, the looming risk of leveraging AI to suppress voter turnout discourages certain groups from exercising their democratic rights.

The age of AI in politics is not a distant prospect; it’s our present reality. As AI continues to infiltrate political campaigns, preparation becomes paramount. Safeguards against potential misuse, such as robust regulations on political advertising and comprehensive voter education initiatives, are imperative.

Moreover, ensuring equitable access to the benefits of AI is a collective responsibility, not just for the privileged few but for all citizens.

Shaping the Future

We stand at a crossroads in navigating the frontier of AI in politics. The tapestry of this technological frontier is woven with both promise and peril. Approaching AI with mindfulness and foresight is key to ensuring it strengthens, rather than undermines, our democratic foundations.

The future of politics rests in our hands, and our decisions today will mold how AI shapes it tomorrow. As we embark on this journey into the heart of technological transformation, let’s embrace the frontier with a blend of caution and curiosity, for the potential of AI in politics has only just begun to unfold.

Poltics

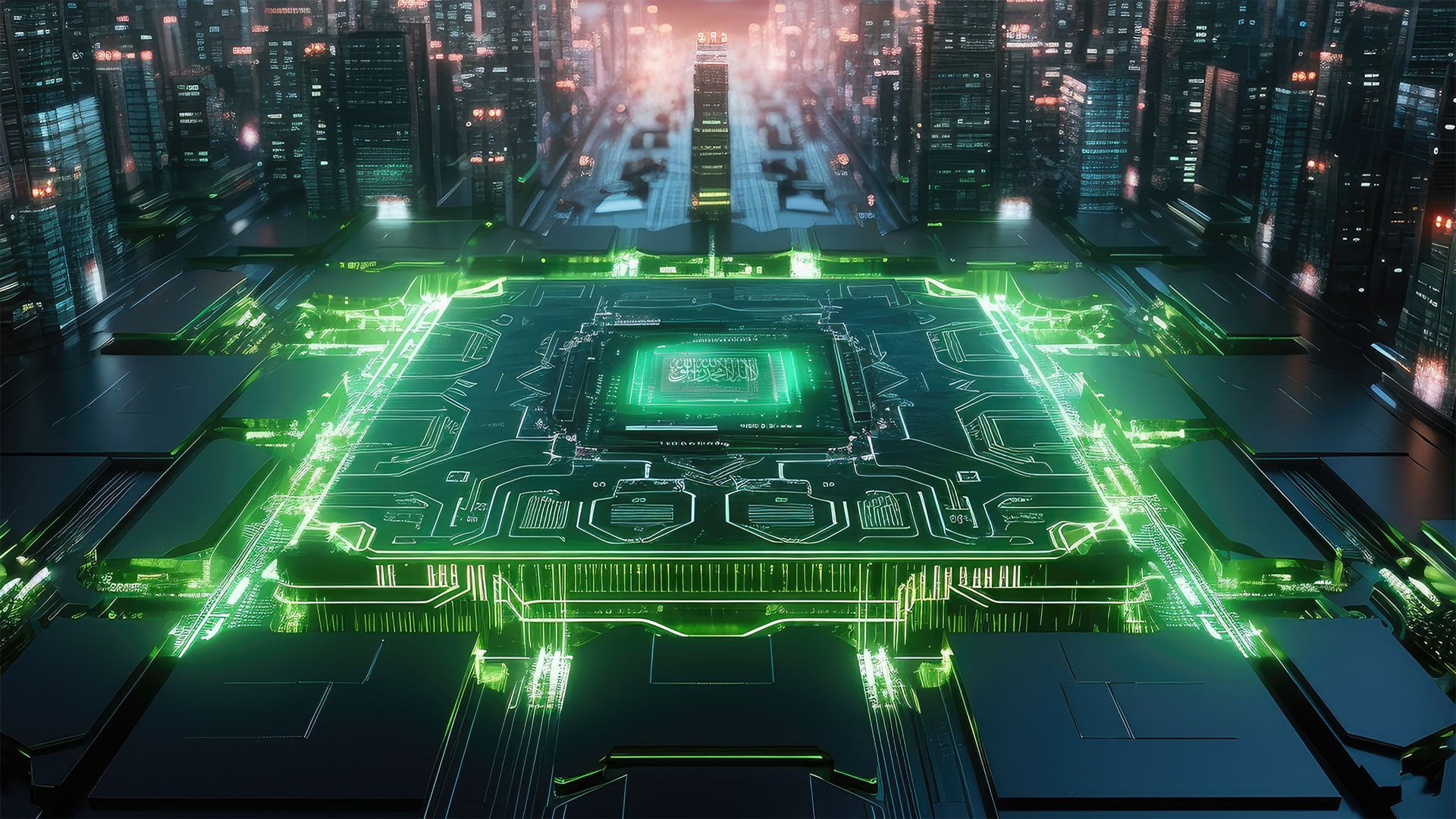

Saudi Arabia’s Tech Revolution: A Blueprint for Global Innovation

Published

2 years agoon

December 27, 2023

In the heart of the Middle East, Saudi Arabia is emerging as a beacon of technological transformation, and its journey towards becoming a tech powerhouse is nothing short of inspiring.

Fueled by the ambitious Vision 2030 initiative, the oil-rich nation is steering away from traditional reliance on oil and embracing a future rooted in digital entrepreneurship.

Diving into the Digital Wave

Picture this: the vibrant city of Riyadh, host to LEAP 2023, where a whopping $2.4 billion in funds were recently announced, signaling a seismic shift in Saudi Arabia’s startup landscape.

According to the Harvard Business Review, venture capital investments are soaring, with a staggering 72% increase in 2021 and 2022, totaling a jaw-dropping $987 million across 144 deals.

What’s propelling this surge? A dynamic blend of a youthful, tech-savvy population, a government dedicated to fostering innovation, and a hunger for digital services.

The General Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) report found that 90% of respondents believe starting a business in Saudi Arabia is a breeze, putting the country at the top among economies.

The Visionary Vision 2030

At the core of this technological renaissance is Vision 2030, an ambitious initiative steering Saudi Arabia towards economic diversification, job creation, and attracting top-tier talent. A key player in this transformation is the empowerment of entrepreneurs.

Vision 2030 has set the stage for a thriving startup ecosystem, with a significant portion of venture capital funding coming from local sources, particularly supporting early-stage ventures in payments and lending.

This newfound support for entrepreneurs has led to the emergence of innovative startups, with the fintech and wealth management sectors taking center stage.

The Kingdom’s commitment to a diverse business landscape is evident, with predictions suggesting the tech, fintech, and e-commerce sectors could surpass $13 billion by 2025.

Government-Led Tech Renaissance

Saudi Arabia’s venture capital boom is not a stroke of luck but a result of strategic government backing. The commitment to the tech industry is palpable through initiatives like LEAP, the world’s largest conference supported by the Ministry of Communication and Information Technology, the Small and Medium Enterprises (SME) General Authority, and the Entrepreneurship World Cup.

Biban, the Kingdom’s global startup, and SME forum is a melting pot for local and international entrepreneurs, investors, and government officials, fostering collaboration and sharing insights.

The government’s commitment goes beyond rhetoric, actively supporting female entrepreneurs. In 2021 alone, 139,754 new commercial licenses were issued to women, solidifying Saudi Arabia’s leadership position in female tech entrepreneurship.

Riyadh proudly hosts the world’s largest women’s university in the educational realm, emphasizing the Kingdom’s commitment to nurturing female talent in STEM fields. Saudi Arabia is not just investing in businesses; it’s investing in the diverse, capable minds that will shape its future.

Venture Capital Landscape

What sets Saudi Arabia apart is the impressive numbers and the blueprint it provides for fostering innovation and entrepreneurial activity. As the venture capital landscape rapidly evolves, it’s becoming increasingly attractive to global investors.

The right combination of government incentives, financial support, and a nurturing business environment positions Saudi Arabia as a potential central hub for tech startups and innovative technologies.

As we witness Saudi Arabia’s tech revolution, other countries can glean valuable insights to foster innovation within their borders. Here are key recommendations inspired by Saudi Arabia’s success:

- Create a supportive business environment: Governments should ensure entrepreneurs have access to crucial resources like capital, mentorship, and networking opportunities. Investing in educational initiatives will equip current and aspiring entrepreneurs with the skills and knowledge needed for success.

- Encourage Public-Private Partnerships: Collaborations between governments and the private sector can provide startups with the necessary resources and infrastructure to flourish. These partnerships stimulate innovation, create jobs, and contribute to economic growth.

- Incentivize Venture Capital Investments: Governments should incentivize venture capitalists to invest in early-stage startups by offering tax breaks and other financial incentives. This approach encourages risk-taking and contributes to overall economic activity.

- Nurture the Culture of Entrepreneurship: Creating an environment that celebrates entrepreneurship is vital. Organizing events and forums that bring together entrepreneurs, investors, and key stakeholders fosters a culture of collaboration and innovation.

As Saudi Arabia charts its course into the digital future, it stands as a testament to the transformative power of visionary initiatives and unwavering government support.

The Kingdom’s venture capital boom is not just a regional phenomenon but a global inspiration. By embracing the lessons from Saudi Arabia’s success, nations worldwide can pave the way for their own tech renaissance, fostering economic growth, innovation, and a brighter future for generations to come.

The journey towards a tech-powered tomorrow starts with a blueprint, and Saudi Arabia is handing the world a roadmap to success.

Poltics

Gaza Conflict: A Mirror Reflecting Broader Middle Eastern Unrest

Published

2 years agoon

December 11, 2023

The Gaza crisis stands out as a pivotal point in the Middle East, a region known for its historical conflicts and political unpredictability, sparking discussions and raising concerns about the appropriate responses to such complex situations.

Whether to align with popular trends or maintain a neutral stance is a matter of strategic importance, especially considering the intricate web of issues entwined with the crisis.

Gaza’s turmoil reflects the historical conflicts and instability of the Middle East.

The origins of extremism in the region can be traced back to significant global events, notably the American-led wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. These conflicts, which began in 2001 and 2003, respectively, not only disrupted the political landscapes of these countries but also laid the groundwork for extremist ideologies to flourish. Mosques, homes, and educational institutions across the region became hotbeds for such radical thoughts, deeply impacting the societal fabric.

The Arab Spring of 2011 further complicated this scenario. Initially perceived as a movement for democratic reform, it soon transformed into a catalyst for the spread of extremist groups. Countries like Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, Yemen, and Syria, each with unique challenges, became arenas for these ideologies to evolve and expand their influence.

The current situation in Gaza is a continuation of this ongoing struggle. It’s not an isolated conflict but a part of a larger pattern of regional unrest, similar to the situations in Afghanistan, Iraq, and the nations affected by the Arab Spring. The conflict in Gaza, therefore, is both a result and a catalyst for the broader geopolitical dynamics in the Middle East.

American-led wars laid the foundation for extremism to thrive in the region.

The Gaza crisis has elicited various responses from countries in the Middle East, each reflecting their unique political landscapes and ideologies. Saudi Arabia’s approach is a notable example, as it has taken a firm stance against the Israeli attacks, demonstrating this through diplomatic efforts and significant humanitarian aid. This is a marked shift from its previous approach, where extremist ideologies often found a voice in public platforms such as schools and the media.

Other countries have also responded in various ways. For instance, Egypt, often seen as a key mediator in Israeli-Palestinian conflicts, has attempted to broker ceasefires and engaged in diplomatic discussions to de-escalate tensions. Similarly, Jordan, which has a significant Palestinian population, has condemned the attacks and called for international intervention to resolve the crisis.

However, some governments have chosen to capitalize on the crisis by amplifying extremist rhetoric, using it as a tool to galvanize public support. Though seemingly effective in the short term, this strategy often leads to unintended consequences.

The rhetoric can spiral out of control, exacerbating tensions and sometimes backfiring on the regimes themselves. For example, in Iran, the government has historically used such situations to bolster its stance against Israel and the West, often leading to heightened domestic and international tensions.

Gaza crisis highlights the ongoing struggle and regional unrest in the Middle East.

Turkey’s position regarding the Gaza crisis, while diplomatically inclined towards advocating peace and stability, is multifaceted, especially considering its continued trade relations with Israel. Despite adopting a stance that favors dialogue and a peaceful resolution to the conflict, Turkey maintains economic ties with Israel, a decision that has sparked significant protests among its population. This aspect of Turkey’s policy reflects a complex balancing act, wherein it seeks to maintain its regional and international economic interests while positioning itself as a mediator and advocate for the Palestinian cause.

The protests in Turkey against this continued trade indicate a divide between the government’s diplomatic and economic policies and the public sentiment towards the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. This situation underscores the challenges faced by Turkey in navigating the intricate dynamics of Middle Eastern politics and public opinion.

Saudi Arabia’s response to Gaza crisis marks a significant shift in regional diplomacy.

In today’s digital age, the role of media in shaping public opinion, particularly regarding extremist discourse, cannot be overstated. Extremist propaganda has become more sophisticated and organized, reaching wider audiences more effectively than before. This evolution presents a significant challenge to maintaining regional stability and countering extremist narratives.

Israel’s role in the Gaza conflict is also a point of contention. The military actions in Gaza, which include targeting civilians, are viewed as brutal acts of retaliation. Such actions not only exacerbate the humanitarian crisis but also serve to bolster the extremist narrative, potentially increasing their support base.

Navigating the complexities of the Gaza crisis and the broader context of extremism in the Middle East demands a nuanced and multifaceted approach. Nations must carefully consider their responses, balancing the need to address immediate crises with the long-term goal of promoting stability and countering extremism. The path forward is fraught with challenges, but with thoughtful engagement, there is hope for a more peaceful and stable region.

Poltics

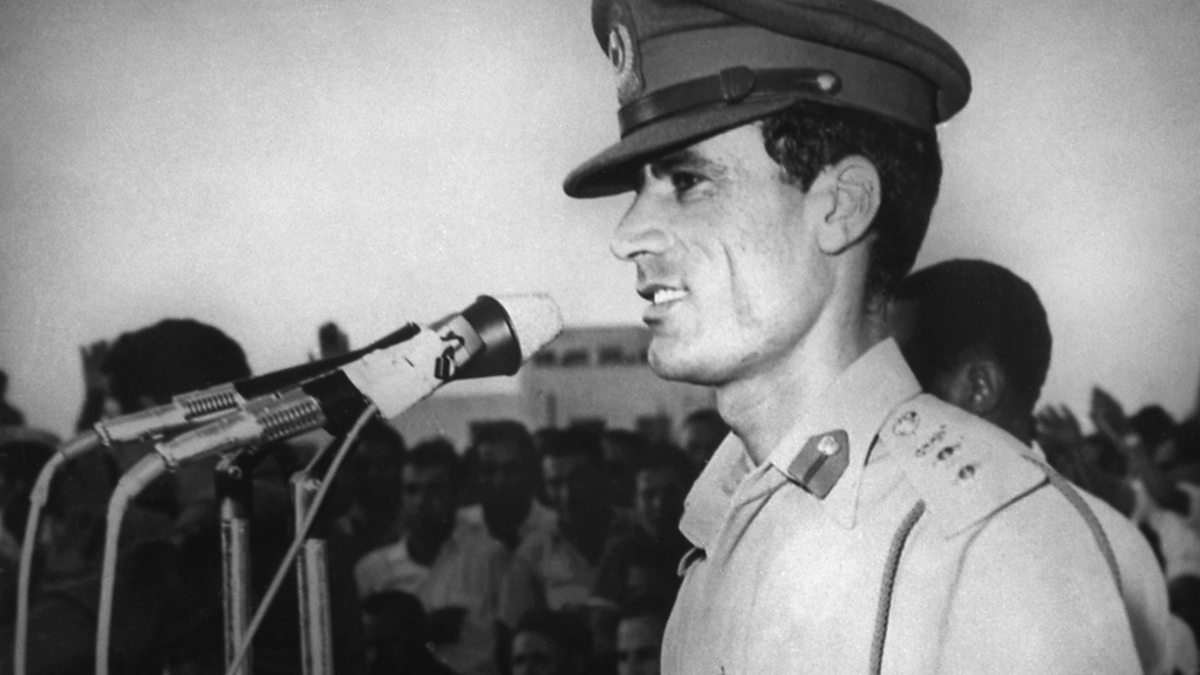

From Unity to Split: Is This Libya’s New Chapter?

Published

2 years agoon

September 17, 2023

In the tumultuous wake of the Arab Spring, Libya, a country once on the cusp of emerging as a thriving democracy, was mired in conflict and chaos. Its transformation from a dictatorship under Gaddafi to a beacon of hope after 2011 was short-lived.

A few years after its pioneering elections, Libya plunged into a civil war, casting a long shadow over its prospects for unity and progress. Today, nearly a decade later, the country remains divided, almost as if cleaved into two semi-independent states.

This division isn’t just geographical but permeates deep into the socio-political fabric of the nation. Exploring the potentiality of this division and its implications in the contemporary context becomes crucial to understanding Libya’s future trajectory.

Historical Precursor to Division

To decipher Libya’s present and potential future, revisiting its past is essential. King Idris took control of an impoverished country after gaining independence from the colonial grip of Britain and France in 1951.

But fortune favored Libya in 1959 with the discovery of oil, revolutionizing its economic landscape and catapulting it into a significant global player in the oil market.

Gaddafi’s ascent to power in 1969 marked a new chapter in Libya’s history. His overthrow of King Idris and establishment of the Libyan Arab Republic were met with initial acclaim. Gaddafi’s anti-Western stance and efforts to distribute the nation’s burgeoning oil wealth were particularly appreciated, especially in the Western regions, which felt sidelined during King Idris’s reign.

However, as the 1970s progressed, Gaddafi’s increasing autocratic tendencies and international isolation caused domestic disillusionment and international disdain. His eventual downfall during the Arab Spring was dramatic and symbolic, marking the end of an era.

Potential Division of Libya

The ousting of Gaddafi, while a watershed moment, ushered in a new set of challenges. Democratic aspirations led to anarchy, culminating in the Second Libyan Civil War.

The emergence of General Khalifa Haftar and his Libyan National Army, controlling the eastern part of Libya, has accentuated the divisions within the nation. This schism isn’t merely a product of recent events but has deep historical roots.

Before its colonization by Italy, Libya was fundamentally divided into three distinct regions: Tripolitania, Cyrenzia, and Fezan. The undercurrents of tension between these regions, particularly between Tripolitania in the west and Cyrene in the east, have consistently shaped Libya’s political history.

The palpable tension between the eastern and western regions can be traced back to King Idris’s reign and even more starkly during Gaddafi’s rule. The eastern region’s resentment over what they perceived as favoritism towards the West under King Idris and Gaddafi’s Western-based governance stoking unrest in the east paints a clear picture of a nation perpetually torn between its two halves.

Given this historical context, splitting Libya into two or three nations doesn’t seem far-fetched. It could be envisaged as returning to its pre-colonial roots, with Cyrenzia and Tripolitania as two separate entities or incorporating Fezan to form a third. However, this proposition isn’t devoid of challenges.

Contemporary Context and Implications

The modern Libyan landscape is a tapestry of political maneuvering, resource conflicts, and foreign interventions. Its split visage, with General Khalifa Haftar’s Libyan National Army controlling significant portions of the nation, particularly the oil-rich sectors, casts a challenging prospect for those envisaging a simple geographical division.

One of the primary challenges in this context is the nation’s vast oil reserves. Beyond their evident economic implications, these oil fields have emerged as symbols of power and sovereignty.

Their strategic importance cannot be overstated, and control over these fields can dictate the course of negotiations and potential compromises. Any division that doesn’t account for a balanced distribution of these resources risks economic imbalances and the potential for renewed conflict.

Yet, it’s not just the tangible assets that pose a challenge. Though tumultuous, decades of shared governance have resulted in a mingling of cultures, businesses, and familial ties that crisscross the imagined boundaries of the East and West.

Severing these connections or enforcing a division without considering the human implications can lead to displacement, social upheaval, and a humanitarian crisis. The social fabric of Libya, woven over years, cannot be easily torn apart without repercussions.

Furthermore, the international stake in Libya’s future further muddies the waters. Foreign interventions, both overt and covert, have played a significant role in shaping Libya’s post-Gaddafi landscape.

International players have backed different factions, seeking a favorable outcome that aligns with their geopolitical interests. Any division or restructuring would necessitate navigating this intricate web of international relationships, ensuring that Libya’s sovereignty isn’t compromised in the bargain.

Given these considerations, the contemporary context doesn’t lend itself to facile solutions or swift decisions. The path ahead is fraught with complexities, requiring a nuanced approach that integrates Libya’s historical legacy and its modern-day intricacies.

Libya’s Crossroads

As we stand at this crossroads of history, the potential division of Libya raises more questions than it answers. Can a split ensure lasting peace and prosperity? Or will it be a band-aid solution to a deeper, festering wound? The intricate balance between historical justification and contemporary practicality is precarious.

What’s unequivocal is that Libya’s current state, divided and in turmoil, is untenable in the long run. Whether it moves towards a unified democratic nation, heals its east-west rift, or splits into separate entities, the fundamental objective should be the well-being and progress of its citizens.

It’s a journey fraught with challenges, but with dialogue, understanding, and a commitment to peace, Libya can chart a course toward a brighter future.

Poltics

Europe’s New Horizon: Expansion Amid Geopolitical Shifts

Published

2 years agoon

September 17, 2023

The European Union (EU), a formidable consortium of 27 member nations, is at a crucial juncture. European Council President Charles Michel recently voiced an ambitious proposal to expand its membership to as many as 36 by 2030.

This proposition, though ambitious, illuminates a strategic and moral imperative in the face of geopolitical shifts and the changing landscape of global politics.

Aspirations of New Members

The aspiring members are primarily from two distinctive groups: The Western Balkans and the Association Trio. The Balkans, comprising Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Serbia, have long been seen as potential EU entrants.

Their aspirations date back to 2003 when the EU confirmed that the Balkans’ future aligns with the European vision.

Meanwhile, the Association Trio, including Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia, has gained prominence due to recent geopolitical events. After the harrowing Russian invasion of Ukraine, these nations submitted formal applications to join the EU.

Ukraine and Moldova have been granted candidate status, while Georgia remains a potential candidate.

The Complexity of EU Accession

Joining the EU is no simple feat. It requires rigorous alignment with the EU’s standards, encompassing various sectors such as justice, security, agriculture, etc. Each prospective nation undergoes a complex procedure, beginning with being granted candidate status.

Following this, every existing EU member must agree to initiate formal negotiations unanimously. This unanimous agreement can sometimes become the first major hurdle in the process.

Furthermore, throughout the negotiations, the candidate nation must upgrade its administrative, institutional, and governance infrastructure to meet EU benchmarks. Given the vast disparities in governance, economic practices, and political structures, this transformation can be long-winded.

Take North Macedonia, for example. It only settled its naming disagreement with Greece in 2019. Another dispute with Bulgaria took until 2022 to resolve. Similarly, Albania’s candidature is intricately linked to North Macedonia’s, causing further delays.

Kosovo’s journey towards EU membership is also riddled with complications, given that several existing EU nations, including Spain, Greece, and Romania, don’t recognize its independence.

Evolving Attitudes towards Expansion

Over the years, enthusiasm for EU expansion has ebbed and flowed. The 2004 inclusion of countries like Poland and Hungary, which lately have been perceived as not meeting EU standards on democracy and the rule of law, made several Western European nations hesitant about further enlargement.

However, Russia’s aggressive actions in 2022 drastically altered the landscape. With its invasion of Ukraine, the discussion around EU enlargement transformed from a bureaucratic matter to a pressing moral duty.

As Austrian Foreign Minister Alexander Schallenberg aptly summarized, expansion became about “exporting and safeguarding a model of life” rooted in free and open Western democracies.

The growing sentiment within EU corridors is that the delay in integrating potential members, particularly those from the Balkans, renders them susceptible to Russian influence. This geopolitical nuance has renewed enthusiasm for enlargement.

The Road to 2030: A Delicate Balance

With renewed vigor towards enlargement, timelines have become a topic of intense discussion. While Charles Michelle envisions 2030 as a plausible deadline for the expanded EU, the European Commission seems more cautious, emphasizing the merit-based nature of accession rather than adhering to a strict timeline.

This cautious approach became evident when the EU rejected Ukraine’s request for an expedited accession process, highlighting the intricate balance between geopolitical urgencies and procedural prudence.

However, the expansion discourse isn’t solely about the readiness of candidate countries. The EU itself stands at a crossroads, needing introspection and reform. The current structure and mechanisms of the EU might be ill-equipped to manage an expanded roster of member nations.

For instance, with the unanimous decision-making process in various policy areas, adding more members might further complicate an already intricate decision-making procedure.

Prominent EU nations like France, Germany, and Italy are pushing for streamlined decision-making through qualified majority voting.

This would mitigate the power of individual nations to stall vital decisions—a scenario evidenced when Hungary stalled decisions related to Russian sanctions.

Moreover, the EU must address internal policy challenges before significant enlargement. The bloc’s Common Agricultural Policy will need recalibration, especially with major agricultural producers like Ukraine on the horizon.

The EU needs introspective recalibration for tariff adjustments, budget realignments, and institutional reforms.

Dreams, Dilemmas, and Decisions

The aspiration for an expanded European Union is more than just increasing numbers; it’s about fostering a collective vision of democracy, open governance, and mutual growth.

While the road ahead is filled with challenges from aspirant nations and within the EU, the benefits of a united and expanded European entity can’t be overlooked.

The coming months will be pivotal in shaping the future of Europe and its role in the world. Whether or not the 2030 vision is realized, this decade’s discussions, debates, and decisions will undoubtedly chart the course for a renewed and revitalized European Union.

Fenikss Casino: Kā Veikt Reģistrāciju un Pirmo Iemaksu

Slottyway PL Nowoczesne kasyno online dla polskich graczy

Unlocking the Power of Smart Devices: What You Need to Know

Is a New Era of United States-China Space Collaboration Possible?

Can smart technology unlock a sustainable future?

Start Your Day Right: The Benefits of a Clutter-Free Desk

Emerging Titan: India’s Strategic Move on The Global Chessboard

Use these services to get free cloud space

From Unity to Split: Is This Libya’s New Chapter?

New Revolution in MENA Region: FAST and Ad-Supported

Navigating The New Silk Road: A Ten-Year Retrospective

How Technology is Reshaping Modern Warfare

Trending

-

Poltics2 years ago

Poltics2 years agoEmerging Titan: India’s Strategic Move on The Global Chessboard

-

Technology3 years ago

Technology3 years agoUse these services to get free cloud space

-

Poltics2 years ago

Poltics2 years agoFrom Unity to Split: Is This Libya’s New Chapter?

-

Technology2 years ago

Technology2 years agoNew Revolution in MENA Region: FAST and Ad-Supported

-

Poltics2 years ago

Poltics2 years agoNavigating The New Silk Road: A Ten-Year Retrospective

-

Technology2 years ago

Technology2 years agoHow Technology is Reshaping Modern Warfare